Fixed income

Thoughts on the Dutch pension system reforms

Back to all

In theory, the reform of the Dutch pension system from defined benefits to a defined contribution could be a shadow hanging over the longer end of European interest rate curves. But even there, we have known for numerous years that this reform was going to happen. Over those years, this reform has been used as an easy explanation for interest rate moves, especially when no other clear catalyst was available.

Over the last few weeks, we believe this is again the case, although we do have more clarity about how much exposure these pension funds have towards European interest rates and when the transition will happen.

In practice, the situation is very different. The market’s main fear is that all these long-end government bonds will come to the market at once and that this will lead to a broad-based sell-off in the long end of European interest rate curves. However, we do not agree, based on three main points.

The first point is that Dutch pension fund managers have as a goal to provide their investees with a positive return, independent of the pension system being defined benefit or defined contribution. Consequently, these pension fund managers know that there is a risk that if they were to sell their long-end bonds to the market, this would be at an unfavourable price and hence could lead to a lower fund return. As such, they will do everything possible to avoid having to sell their long-end exposure in adverse market circumstances, as the pension system does not imply forced selling. The way they will do this is by using the same interest rate swaps they have always used to limit their asset-liability mismatch. This way, they are able to adapt their long-end interest rate exposure without having to sell cash bonds. Consequently, when the new pension proposal is signed into law, the actual cash flow in the market should be limited and spread over time. This is because the pension system transition covers the period between now and January 2028, hence implying that even if bonds are sold, it would be spread over a multi-year period.

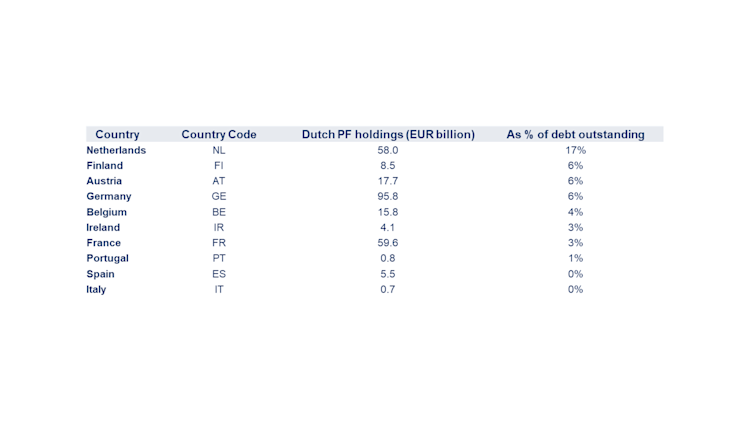

The second point is that we should not worry too much about a broad-based sell-off in the long end across European government bonds, as the amount these Dutch pension funds hold in the long end is very concentrated. Like many investors, they also suffer from a home bias and are most exposed to their own government bonds. As you can see in the table below, they hold 17% of the outstanding in the long end of Dutch government bonds, followed by much smaller allocations towards Austrian, Finnish and German bonds, while having almost no exposure to Spanish and Italian bonds. As such, if there were to be any reaction, it would be on Dutch government bonds.

Dutch PF ownership of central government bonds

Source: Goldman Sachs FICC and equities, 2024

Finally, the expectation that the full government bond exposure of these pension funds will be removed does not take into account the relative attractiveness of European interest rates in general, but especially at the longer end of the curve. We are no longer in a zero or negative interest rate environment, and the policy normalisation by the ECB has made European government bonds once again a core building block for investors, as yields are finally at attractive positive levels. Especially in the long end, where even the 30-year German bond yields more than 3.2% and where Italy yields 4.5%, investors can lock in very attractive yield levels for very long-term periods.