Fixed income

The past, present, and future of EU fiscal policy

Back to all

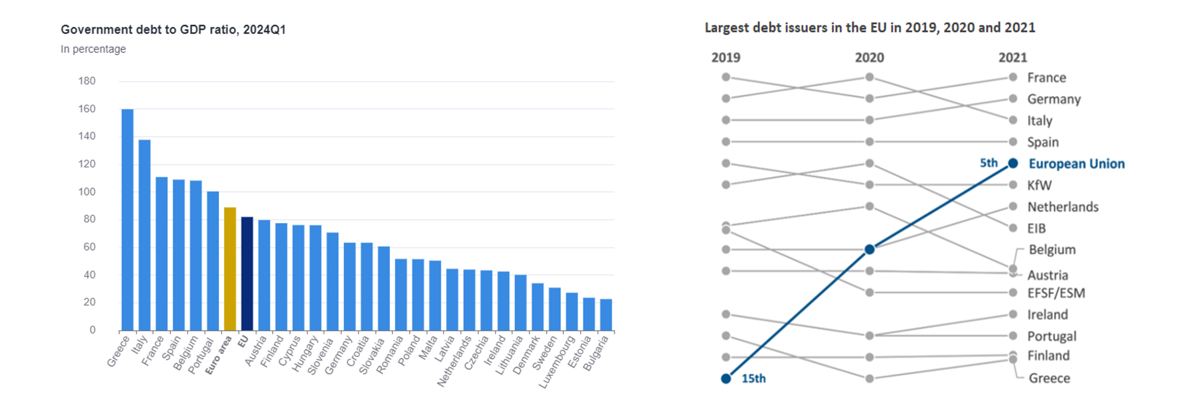

A 60% debt-to-GDP ratio and a 3% annual deficit limit, these are the two fiscal benchmarks included in the EU treaties to ensure countries maintain sound public finances. Today, the total debt-to-GDP ratio in the Eurozone stands at 89%, with major economies like France and Italy even having ratios higher than 110%. Looking forward, what does this escalation mean for future fiscal policy in the Eurozone, and what are the implications for markets?

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Commission (EC) invoked the general escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), allowing member states to temporarily bypass strict budgetary requirements without facing sanctions. This measure was intended to provide countries with the flexibility needed to address the severe economic and social impacts of the pandemic. On top of that, the EC also introduced the Next Generation EU (NGEU) recovery plan. Through a combination of grants and loans, no less than EUR 800 billion has been made available to member states to support their economic recovery and invest in shared priorities such as climate change and digitalisation. This marked a significant milestone for the European Union as it was the first time they launched a joint fiscal program on such a meaningful scale. In no time, the EC, acting on behalf of the EU, became one of the largest debt issuers in Europe.

Source: Eurostat, European Commission, ECA

The fiscal situation post-pandemic: national flexibility vs. supranational rigidity

Four years have passed, and both the sanitary and economic environments have changed. The EU is once again urging member states to cut their high levels of debt, and the NGEU has reached its halfway point. Are we reaching the end of a fiscally expansionary period? The answer is no.

Regarding federal debt, it is true that the EC is no longer turning a blind eye to excessive deficits. However, keeping in mind the budgetary challenges related to aging populations, climate change, and additional defence spending, the EC recently proposed to the European Parliament to tweak the two-decade-old fiscal rules. Not only will they deviate from their former one-size-fits-all framework by tailoring fiscal recommendations to the debt sustainability of each member state, but they will also allow more time to cut public debt and create incentives for necessary public investments. The old rules required, for example, member states with a deficit greater than 3% of GDP to cut their deficit to less than 3% the following year and to target a structural deficit of no more than 0.5% of GDP, while the new rules require those countries to shrink their deficit by at least 0.5% per year and to target a structural deficit of no more than 1.5% of GDP. Another concession involves excluding interest expenses from deficit calculations until 2027, recognising that these expenses are set to rise as countries refinance their maturing debt at higher interest rates. These adjustments suggest the EC is shifting towards a more flexible approach in addressing today’s challenges.

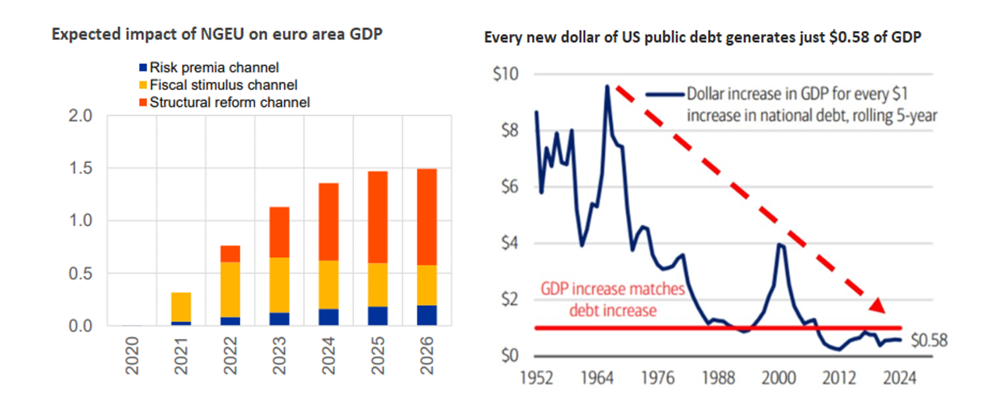

With regards to supranational debt, it can be noted that almost two-thirds of the NGEU budget has not been paid out yet. The reason is that the largest part of the NGEU is being implemented through the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), which is performance-based. This means that member states can only request disbursements when they have achieved predefined milestones and targets towards completing the reforms and investments included in their plan. The bullish investor would say that this means there is still a lot of firepower left, while the bearish investor might argue that it is unlikely all funds will be disbursed before the deadline of the end of 2026. This latter view is supported by the fact that payments are often held up due to disagreements on required reforms. In Belgium, for example, funds from the RRF will be used for the construction of the Princess Elisabeth Island, the world’s first artificial energy island that will connect offshore wind farms in the North Sea to the onshore electricity grid. However, the funding is on hold due to a dispute over Belgium’s pension reforms, making the landmark project a good example of how Europe’s bureaucracy and fragmentation hamper its high ambitions. Critics also claim that the economic impact from the investments is often overstated. Due to the time pressure countries face, the capital might not be employed in the most efficient way or might be spent on projects that governments would have undertaken anyway. According to the EC, GDP in the euro area will be up by 1.5% by 2026 if the NGEU is fully implemented. This considers not only the direct impact from the fiscal stimulus but also the result of the required reforms and the lower sovereign risk premia. Based on ECB calculations, the fiscal multiplier will be around unity, which means every euro of public debt generates around one euro of GDP. However, the law of diminishing returns, formulated by economists like David Ricardo, also applies to debt capital: the more you continue to increase debt, the more the impact on GDP will flatten out. This has been clearly visible in the US, where the multiplier has been declining over the past decades with productivity coming down.

Source: ECB, Bankowski et al. 2022 [left]; BofA Research, Investment Committee, Global Financial Data, 2024 [right]

A call for radical change: how the EU can stay competitive

The EU will have to act decisively if it wants to maintain its role on the world stage. China became the second largest economy through decades of aggressive industrial policy and is now securing its spot by investing massive amounts in research to establish dominance in the industries of tomorrow, such as electric vehicles and renewable energies. The US responded to this with substantial fiscal programmes, like the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act. If the EU wants to remain competitive, it will have to catch up quickly. Some politicians and economists suggest transforming the NGEU into a permanent European instrument for initiating joint debts. This could then be used to allocate resources towards common investment needs such as the green and digital transition, but also defence, migration, or even health care. Furthermore, the instrument could be used to stabilise the economy by responding counter-cyclically to economic shocks, as was done with COVID-19. The advantage of doing this at the supranational level is that it can often be done at a lower financing cost while also taking off some pressure from national debt markets. At the time of writing, the spread on 10-year EU bonds is close to those of French bonds, at approximately 50 bps higher than the bund spread. However, the EU has been pushing to have its bonds reclassified as sovereign instead of supranational debt to lower the borrowing cost. By doing this, their bonds would be included in widely followed bond indices such as those of JPM, which would force investors tracking those indices to buy EU bonds. So far, the EU has not succeeded in doing this.

Not all member states back the idea of permanent EU borrowing. The main reason is the risk of moral hazard. Countries like the Netherlands fear that this would limit the financial discipline of the bloc as it encourages countries to take less responsibility for their own budgetary policies and structural reforms. As a result, you run the risk that it boils down to continuous financial transfers from countries with sound fiscal policies to countries that pay less attention to their budget. A much broader restructuring seems needed. As Mario Draghi said, the five-year European mandate should be one of “radical change”. The former ECB president stated that Europe should better leverage its scale to remain competitive. European governments spend, on average, the highest amounts of funds in the world (in percentage of GDP) for the provision of public goods and services. Regarding energy, for example, European companies pay two to three times more for electricity than companies in the US. For telecommunications, Europe counts 34 networks while the US and China have only three and two respectively. A lot of potential lies therefore in network effects. The purchases of raw materials could also be centralised to gain bargaining power and to create a fair level playing field within Europe. Draghi even suggests that the EU should make greater use of tariffs and subsidies “to offset unfair advantages created by industrial policies and real exchange rate devaluations abroad”. The EC already relaxed state-aid rules to support green investments in for example hydrogen, carbon capture, and zero-emission vehicles. However, this disproportionately benefits rich countries that have more money than others. This has also been acknowledged by EU Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, who wrote in a letter that Germany and France accounted for 77% of aid given under looser competition rules introduced during the pandemic. This again shows that short-term measures should make way for thorough long-term restructuring.

Investment implications

Despite the EU borrowing significant amounts from capital markets while countries are already operating far above the fiscal thresholds set out in the EU treaties, economic growth in the Eurozone has been below par compared to competing regions such as the US and China. The EC recently proposed to grant member states more time to cut public debt, while also relaxing the rules around state-aid. However, the consensus is that the EU is doing too little. This is also reflected in financial markets where the Eurozone trades at a forward P/E of 14 versus 22 for the US. While the European stock market has always been trading at lower valuations compared to the American one, the divergence is historically high. This also means that there is plenty of upside potential that could be triggered by a deep restructuring where the EU better leverages its scale. Investors are therefore looking forward to reading Mario Draghi’s recommendations on Europe’s competitiveness, which will be published in the coming weeks. However, given the high level of fragmentation and bureaucracy, one wonders how much of his plan will eventually be implemented. Member states will likely have to take on even more debt to fund economic growth, hereby also trying to offset the adverse impact from worsening demographics on GDP. For bond markets, this does not necessarily mean that the long end of the yield curve will have to go up. Japan is a leading example of this. After decades of near-zero inflation, they have a debt-to-GDP ratio higher than 250% together with very low interest rates. This shows that if inflation remains low, higher debt rates do not necessarily translate into higher interest rates. But to meet this condition, the fiscal stimulus will have to be accompanied by higher productivity.